Finding Ease in the Effort: Strategies for Managing Your Pain

This next part of the series will discuss how you can better manage your pain. When you come to your appointments, there are different hands-on techniques or modalities that we can use to help you with your pain in the short term. But it is important to remember that you only see your physiotherapist for 30 minutes out of your day – the other 23.5 hours are in your hands!

The experience of pain is unique to each person and is based on many factors that we explored in the previous article. As you can see, pain is complex. However, it’s management does not need to be complicated. Pain management is possible through understanding pain and exploring evidence-based therapeutic interventions and self-care strategies.

Exercise is medicine! Many people in pain tend to avoid certain movements and exercise in general. However, there is now an abundance of evidence that has highlighted the positive effects of exercise and physical activity on both acute and chronic pain, overall daily function, and quality of life (1-3). Studies have shown that it can be an effective way to reverse the downward cycle of deconditioning and worsening pain, and gradually over time can help those with persistent pain engage more in activities of enjoyment and daily living with more ease.

It is important to start gradually when beginning to exercise, and avoid pushing too far into pain. At the same time, it’s important to not let the pain scare you; a tolerable amount of pain with exercise is acceptable. It can be helpful to use the 0-10 scale to monitor your pain levels while exercising – if your pain increases by more than 2 points from baseline, you should modify the exercise to make it less provocative and to avoid a flare-up. You may be in a bit more pain for the remainder of the day, and this is okay – so long as the pain goes back to baseline by the next morning. With this approach, over time your pain threshold will get higher and you will be able to tolerate more exercise, slowly but surely. Your physiotherapist is an expert in this and can help to guide you!

Sleep is not for the weak!What came first, the chicken or the egg? That is the ultimate question, and the same thing can be asked of sleep & pain. Recent research has shown that sleep and pain have a bidirectional relationship; meaning they share the same brain pathways (4), and thus influence each other very easily. So – are you sleeping poorly because you have pain? Or do you have pain because you are sleeping poorly?

After only one bad night of sleep, there is a decrease in the pain threshold which means it takes less to provoke it (5). We can think of it like a volume dial; our brains have the amazing ability to dampen the sound signals (turn down the dial) from the nerves in our bodies. With sleep deprivation, that ability to turn down the dial is reduced – therefore, the sound signal of pain increases (6). With sleep deprivation, the ability to cope with pain is hindered and makes everything more aggravated. Getting more sleep is not only crucial for our general health and happiness, but it also can have a protective factor against pain.

Here are a few simple strategies that can help you get a better night’s sleep:

- Keep to a sleep schedule; even over weekends (try to go to sleep and wake up at about the same time every day!).

- Allow yourself time to relax and unwind at the end of the day. Try to dim or turn off lots of the lights in your house in the hour or two before bed to help that melatonin release.

- Turn your heat down – humans are meant to fall asleep when the sun goes down and it gets cooler. Thermostats have made our modern sleep hygiene problematic!

- Reduce the amount of gadgets/screens in your bedroom; they can be a distraction.

Pacing – not too much, not too little, but just right.

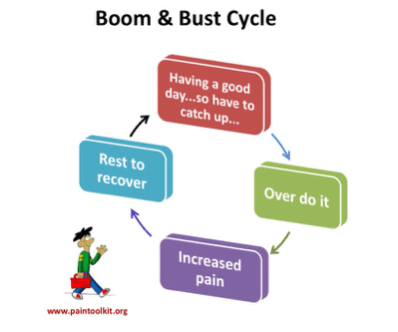

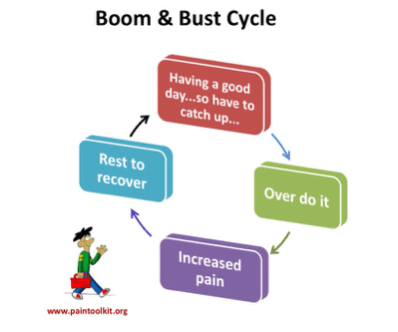

Does this cycle look familiar? Perhaps you wake up one morning and you feel especially great – so you do more activity than usual (catching up on that never-ending to-do list!). However, if your body and brain aren’t accustomed to doing this much, it can trigger a flare-up of your pain, which then forces a prolonged rest to recover. Over time, this can lead to lower and lower tolerances for the activities that you are wanting to do, and can be extremely frustrating.

However, by slowly down initially and avoiding overexertion, you can avoid the “bust” component of the cycle. By doing just enough, over time we are able to improve our tolerance and do more; but if we do too much or too little, our threshold only tends to get lower. It’s a fine line that your physiotherapist can help you walk successfully.

The important steps for pacing are:

- Determine your baseline

- Break up activities into smaller components

- Take frequent, short breaks as needed

- Gradually increase the amount that you do

An example of this would be noticing that your back pain tends to flare up after walking 5km. You then tend to spend the next few days resting, and then when you go out to walk again, your tolerance is no better – sometimes worse. A better strategy would be to either break up your walk into two 2.5km loops; one in the morning and one in the evening to allow adequate time for rest. Or, decrease your loop to 4km at once. If you are able to complete these walks with no “bust” of your pain, then it is a success – and over time, you can build your tolerance back up to 5km, and beyond!

Many individuals have found that when pacing is implemented into their daily routines, it can be very effective in helping things such as fatigue, pain levels, and tolerance of exercise and movement (7). Pacing can be a difficult skill to integrate into your life, and as physiotherapists we are here to help you find strategies that will work best for you.

References

- Hayden JA, Van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G. Systematic review: strategies for using exercise therapy to improve outcomes in chronic low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142(9):776-85.

- Babatunde OO, Jordan JL, Van der Windt DA, Hill JC, Foster NE, Protheroe J. Effective treatment options for musculoskeletal pain in primary care: A systematic overview of current evidence. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0178621.

- Geneen, L., Smith, B., Clarke, C., Martin, D., Colvin, L. A., & Moore, R. A. (2014). Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd011279

- Walker, M. P. (2018). Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. New York, NY: Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

- Walker, M. P., & Stickgold, R. (2009). Sleep and Memory Consolidation. Sleep Disorders Medicine,112-126. doi:10.1016/b978-0-7506-7584-0.00009-4

- Simpson NS, Scott-Sutherland J, Gautam S, Sethna N, Haack M. Chronic exposure to insufficient sleep alters processes of pain habituation and sensitization. Pain. 2018; 159(1):33-40.

- Guy L. Effectiveness of Pacing as a Learned Strategy for People With Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review. Am J Occup Ther. 2019; 73(3): 1-10.